CONTENT WARNING: VIOLENT IMAGERY

Animals have been represented in art from earliest times, emphasising the integral roles they have played within human civilisation as labourers, livestock, and companions. In contemporary society, this representation has come to include the physical use of animals in art, often causing their harm or death in the process. Often, artworks that involve animals hide the extent of the suffering endured by their subjects. If the animal is alive, it appears safe. If it is dead, it is not usually shown as a carcass, but as a representation of how the animal appeared in life. However, there are exceptions, and violence is still a much-used aesthetic in some spheres. For instance, animal rights groups use violence as an effective tool to show the treatment that animals are forced to endure.

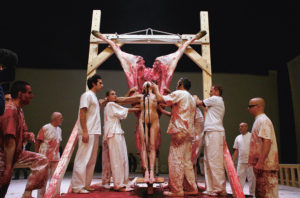

Austrian performance artist Hermann Nitsch does not hide the suffering that he subjects animals to, yet seems far from depicting violence against animals in a way that advances the cause of animal rights groups. Instead, he stages theatrical occurrences that explore themes of religion and war using sometimes horrific—though sometimes beautiful—demonstrations of violence against animals. These instances of bacchanalia involve feasting, drug taking, crucifixions, cult-like attire, animal immolation, and the use of sundry red items as props in ritualistic performances. Nitsch was first recognised by the art community in the early 1960s when he exhibited a skinned and eviscerated lamb crucified against a white wall, with its entrails displayed below. He then went on to stage the Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries nearly 100 times between 1962 and 1998.

Hermann Nitsch ‘Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries’ 1962-1998 (Photograph by Lukas Gansterer, Whitelies Magazine)

Hermann Nitsch ‘Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries’ 1962-1998 (Photograph by Lukas Gansterer, Whitelies Magazine)

Hermann Nitsch ‘Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries’ 1962-1998 (Photograph by Lukas Gansterer, Whitelies Magazine)

Hermann Nitsch ‘Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries’ 1962-1998 (Photograph by Lukas Gansterer, Whitelies Magazine)

Nitsch has been known to create aesthetically pleasing paintings using the blood, bile and excrement of the animals killed during his performances. He has also made many similar paintings using traditional mediums, such as oil, acrylic, watercolour and graphite. The mediums used for these paintings are indecipherable from one another, which shows how the same results can be achieved without harming animals. These works raise important questions not only about how violence against animals figures into the creation of art, but why artists find it necessary to depict real violence rather than a simulacrum of it.

Hermann Nitsch ‘Schuttebild’ 1998, oil and blood on jute

Hermann Nitsch ‘Schuttebild’ 1998, oil and blood on jute

Hermann Nitsch ‘Splatter Painting’ 1986, oil and acrylic on canvas

Hermann Nitsch ‘Splatter Painting’ 1986, oil and acrylic on canvas

Argentinian theorist Osvoldo Romberg asserts that Nitsch is influenced by Sigmund Freud’s and Michel Foucault’s writings on sadomasochism and that his work serves to encompass “[p]urification, therapy and an awareness of death through catharsis and participation” (np). His performances are intended to be a cathartic awakening for the participants, even though they are of an inherently violent nature. One particular work shows the gutted carcass of a pig meticulously attached to the front of a nude, blindfolded woman who is hung from a crucifix. A frenzy of onlookers, dressed in white, hold open what appears to be her stomach as she is pushed along in a procession-style setting. Regarding the role of catharsis in his work, Nitsch has suggested that “[t]he ripping apart of raw flesh should be satisfying and enjoyable as it relieves man of his suppressed desires” (Peled 55).

Nitsch proposes that art should be altruistic and suggests that his work serves to enlighten audiences about the relationship between humans and animals. This relationship is one of collective hypocrisy, with outrage a typical response from people who are otherwise complicit in cultural or aesthetic violence against animals, such as the consumption of meat or the wearing of leather. This would be a poignant observation if Nitsch, who has suggested that his “speciality is the agonizing torture of animals” (np), had sought to prove only that his opponents were not without guilt. However, enlightening his viewers to this fact does not absolve him, or his artwork, of ethical responsibility. This is where difficulties arise, as Nitsch has already demonstrated that actual violence can be simulated to such an extent that it is indistinguishable from the real thing. Nitsch has eschewed artifice in favour of the thing itself, and by doing so become implicated in the violence he depicts.

Nitsch has suggested that “[i]t is our flesh and blood I work with” (Kuhner np), and even though this statement was intended as a metaphor, it should not be taken lightly. His comments recall Sue Coe’s musings about robbing the animal of its identity. Nitsch is not without guilt, and this is a fact that sets him apart from many artists. He proposes that he does not like to kill, that he loves animals, and that the making of his work is very difficult for him. However, the blood that he uses is not metaphorical; it is physical blood taken from a physical animal. It is not an artistic medium, but the thing itself being depicted. He justifies being party to the violence he depicts by claiming that there are “no limits in art. . . . everything can be art” (Nitsch np), and suggests that there is no space for a line to be drawn. His statement takes for granted that actual violence can stand as an artistic representation of violence, and that a thing can stand in for itself as a metaphor. When considering such a view of art, and reflecting upon his previous work, the future of an art removed from the mediating presence of artificiality is unnerving.

Romberg proposes that instead of searching for a reason why Nitsch’s work should or should not exist, we should consider the fact that different people gain different existential experiences when viewing his work, and we should accept it for what it is. This suggests we should not question these performances because they elicit some form of response from viewers. By this reading, art appears to be anything that elicits a response, extending all the way to violence itself. This is a description of an art uncoupled from artifice, an art that encourages the killing of animals for creative endeavour simply because we, as humans, have a desire to understand our own existence and a belief that the death of animals will somehow reveal it. It assumes that one can better understand violence by perpetrating it, that killing could help humanity account for murder.

Works Cited

Kuhner, Herbert. “The Rituals of Hermann Nitsch,” Vienna Net, accessed 19 February 2013, http://viennanet.info/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/the-rituals-of-nitsch.pdf.

Nitsch, Hermann. interview by Jonas Vogt, Vice Magazine (2010), 1 November 2010, http://www.vice.com/magazine/17/11.

Peled, Zoe. “Discussing Animal Rights and the Arts,” Antennae 19 (2011): 55.

Romberg, Osvaldo. “Redemption through Blood,” Slought Foundation, 19 February 2005, http://slought.org/files/downloads/exhibitions/SF_2005%5BNitsch%5D.pdf.

Further Reading

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-04-20/slaughter-show-help-tasmania-economy-mona-david-walsh/8456422

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-17/dark-mofo-bull-slaughter-show-gets-shock-and-bored-response/8627436

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-04-19/controversy-over-hermann-nitsch-dark-mofo-bloody-art-show/8452202

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2017/mar/20/shock-art-can-grossing-people-out-be-considered-an-art-form

https://iview.abc.net.au/collection/shock-art

https://www.amazon.com/Visual-Shock-History-Controversies-American/dp/1400034647

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4oxg2v4117o